Morelia is the capital city of Michoacán, one of the most affected states in terms of drug-related violence in Mexico. It is in this region where the so called “Mexican Drug War” started in December of 2006, when the Federal Government deployed its first major operation involving military forces against drug cartels. After 13 years this conflict has accumulated

around 250,000 deaths,

more than 61,000 disappearances and countless violent episodes that have severely damaged the social, cultural and economic reality of the country.

In this context, in 2016 I was appointed to coordinate a diagnostic for a pilot neighbourhood improvement program of the Municipal Institute of Planning of Morelia (IMPLAN). The objective was to identify appropriate policy interventions for improving the quality of life in marginalized neighbourhoods of the city. At that time Morelia was one the municipalities with higher crime rates in the state, naturally affected by the spiral of violence released throughout the country. Just one year before, the

“most wanted” drug lord of those days, leader of a Michoacán-based cartel, was captured in the peri urban fringe of the city where his organization used to operate.

We selected two study-cases where we conducted a participatory process in order to identify the most important issues in the eyes of the neighbours. As it was a flexible pilot, we had the possibility to modify the approach and methods of the diagnostic as we were conducting it. This allowed us to learn from the participants involved in the exercise and to adapt the process to better meet their needs and interests.

The Lomas del Durazno gap

One of our most interesting experiences was in Lomas del Durazno, a neighbourhood informally settled in the 1980s at the core of an area that now is characterized by high rates of social and economic marginalization. Here we ran a set of surveys and a participatory workshop to identify the main challenges and opportunities of the community. Everything was going according to our plans; however, when we checked the preliminary results, we noticed a gap that made us redesign our approach.

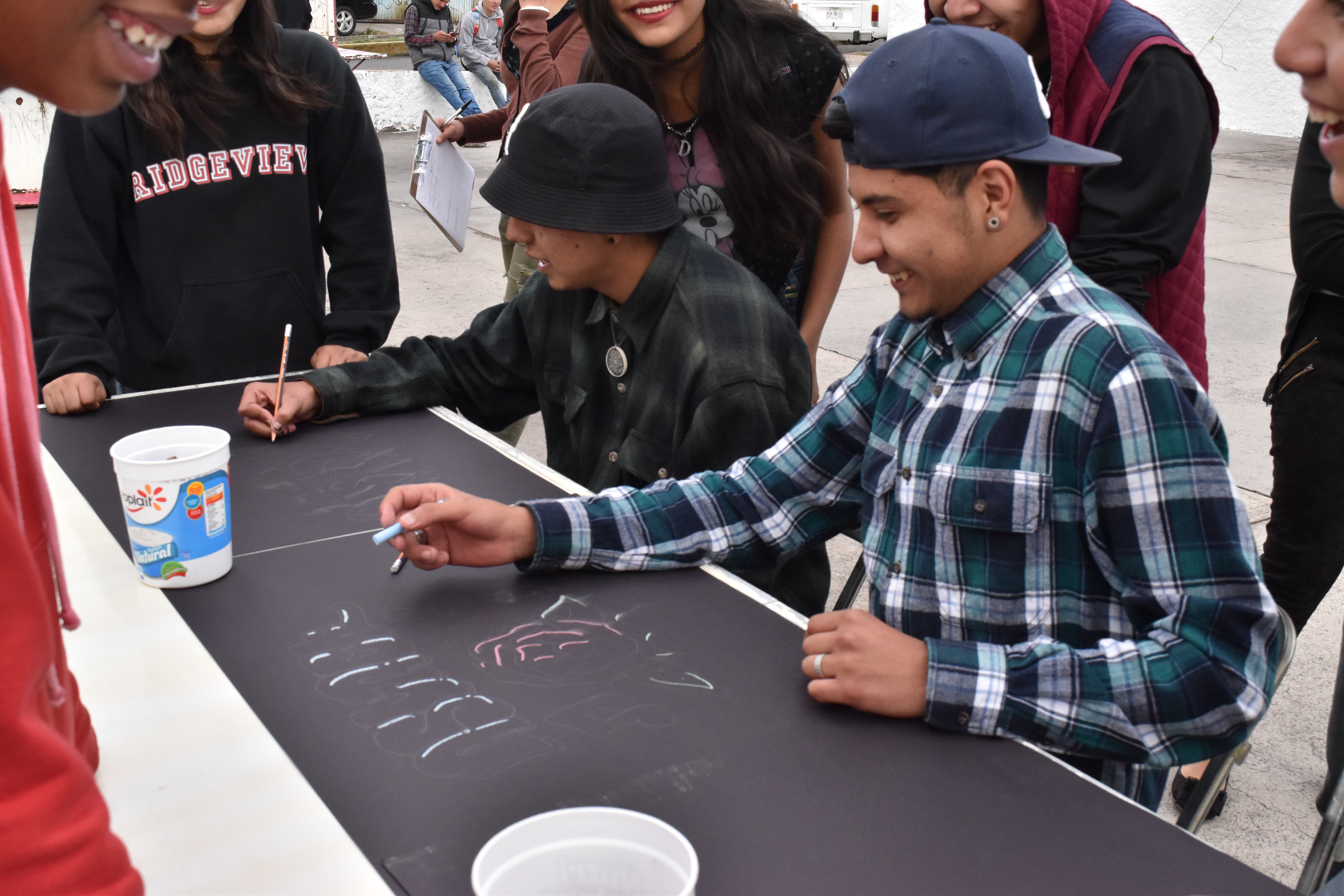

Participatory workshop with neighbours of Lomas del Durazno.

Participatory workshop with neighbours of Lomas del Durazno.

Participatory workshop with neighbours of Lomas del Durazno.

Participatory workshop with neighbours of Lomas del Durazno.

Our data was pointing to youths of the neighbourhood as the main cause of insecurity. However, we noticed that young people hardly participated in our pre-designed interactions with the community. They were neither answering our house-to-house surveys nor attending our workshops. We acknowledged that our methods were not only failing to reach one of the most important population groups in that area but also the specific group alleged as the problem at hand.

Urban Talent: Graffiti, rap and skateboarding

Fortunately, during one of our workshops we met Yesenia, a 19-year-old local leader who helped us to connect with the young population of the neighbourhood in order to define participatory exercises of their interest. As a result, and with the help of a small group of committed neighbours and a local NGO working in the area, we organized an event where the alleged offenders had the opportunity to practice three things they liked: graffiti, rap and skateboarding.

Youths of Lomas del Durazno participating in the Urban Talent event.

Youths of Lomas del Durazno participating in the Urban Talent event.

The event, named “Urban Talent”, helped us to better understand the perspective of the youths in relation with their neighbourhood. As a result of our conversations with them and their artistic expressions, the participants reported their most pressing issues: addictions, crime, deaths and lack of safe spaces and opportunities for recreation. We identified that while older people expressed insecurity as the main problem in the neighbourhood; for youths it was violence, and they confessed to be the main victims of it.

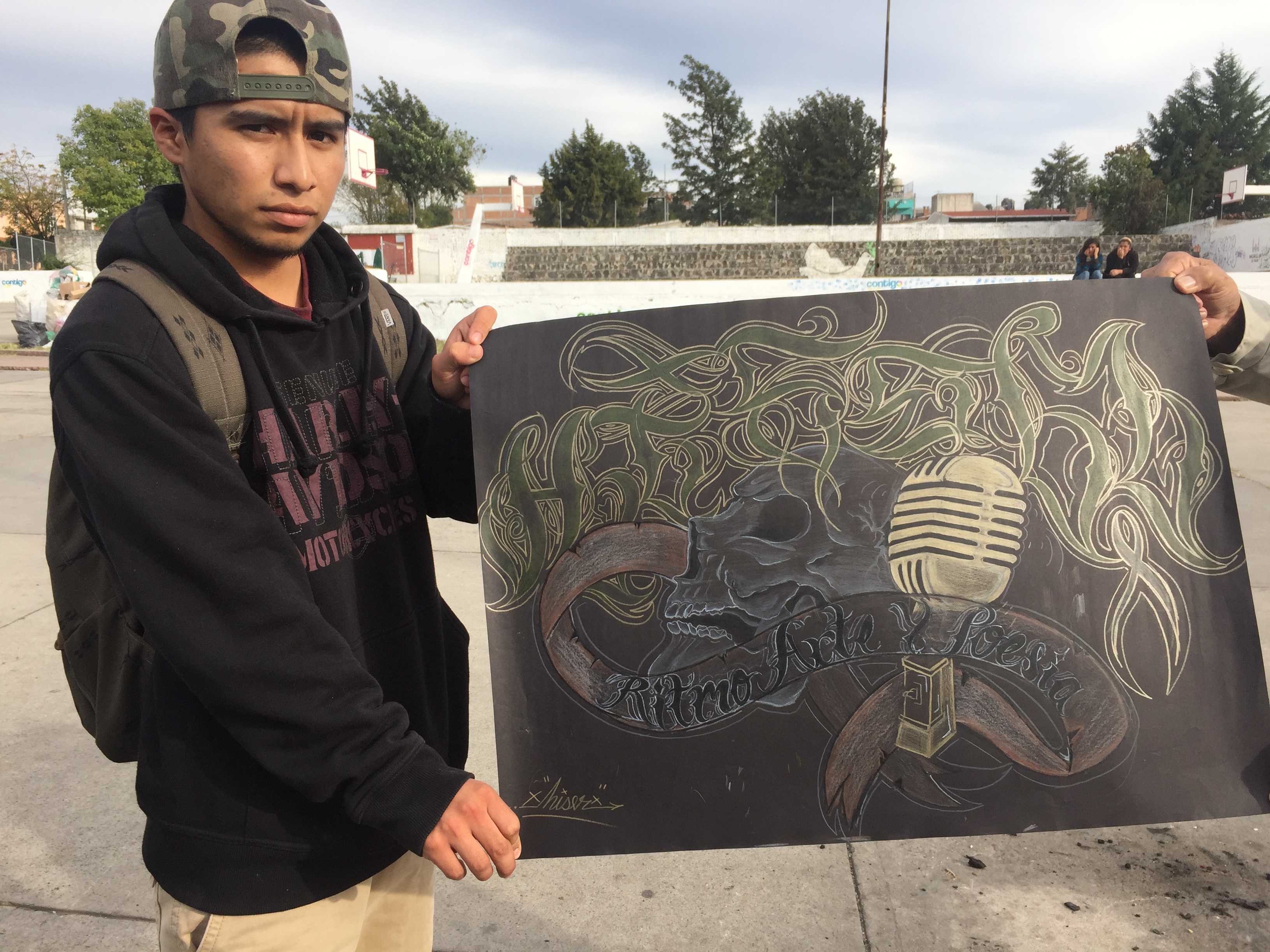

Rigo, a student of veterinary medicine that won a graffiti contest organized during the event, explained his artwork, which portrayed a skull and a microphone. “

More time for art, less time for death”, he wrote on the wall where he painted his graffiti mural:

“… The skull represents death, which is very frequent here in the neighbourhood due to crime, and the micro is for many a way for escaping the streets… basically withdrawing from vices…”

Rigo and his artwork

Rigo and his artwork

Rigo and his artwork

Rigo and his artwork

Redesigning our participatory process permitted us to learn how the stereotypes associated with the youths and their practices were revictimizing them. In view of the older (and relatively more powerful) population, youths were linked to endemic crime alongside drug and alcohol consumption and were therefore negatively judged. However, this point of view did not consider how the lack of educational, professional and leisure opportunities in the area could be relegating them from a different path of life.

The perils of ignoring power structures

As Bill Cooke and Uma Kothari mention in their 2001 book “

Participation: The New Tyranny?”, ignoring the relative structures of power among the actors involved in a participatory process can lead to providing opportunities only for those in more powerful positions. In this sense, our policy recommendations after the diagnostic were focused on providing means for practicing the sportive and cultural activities already preferred by the youths of the neighbourhood in order to protect them against addictions or gangsterism, activities that when escalated may drive them closer to the formal organized crime groups operating in the city.

Understanding the power dynamics that undermine the voices of underrepresented populations in participatory processes is essential as a development practitioner, particularly where stereotypes are solidly present in public conversation. Early in January of this year, for example, the Mexican President

Andrés Manuel López Obrador stated in his daily press conference that “

those who commit violent crimes are generally under the influence of drugs and for the most part are youths”, after being questioned about the high rates of murders and disappearances of kids and adolescents.

Tools for social inclusion

While half of the missing people since the beginning of the “Drug War” are youths, we cannot ignore their voices in any development planning process. As in the case of Lomas del Durazno, Morelia, conducting open and flexible participatory processes can be useful for understanding different perspectives around the social issues that shape life in cities. Therefore, they can be tools for social inclusion in decision making and policy design.

The author would like to thank all the people involved in the project as well as IMPLAN Morelia for the permission for sharing their pictures.

Find out more about

Participatory Methods along with resources to generate ideas and action for inclusive development and social change.

This is part of a series of blogs written by current IDS masters students and PhD Researchers. Look out for other blogs in this series, including: Barricades and democratic tsunami in Barcelona;

Muxes, the third gender that challenges heteronormativity;

That Night a Forest Flew;

Eco-anxiety and the politics of hope: a reflective opportunity to build resilience;

About Greta Thunberg and silenced environmental leaders; From alleged offenders to confessed sufferers: Participatory process in action;

Women’s struggle in Afghanistan: An Insight from a Human Rights perspectives;

Feminist Latin American movements demanding sexual and reproductive health and rights;

India’s Progressing Ambitions in Development Finance;

The British voting system for disabled voters is broken: How to fix it… plus others to follow on- Rwanda on a participatory theatre project, and USAID’s digital strategy.