In the last years, technology has changed the way in which we live and interact with others. However, some processes like paper voting originated in the Roman society in 139 BCE and have barely changed since their inception. This traditional system is relatively secure and reliable, but its accessibility is limited. While for most people voting in electoral polling stations is a mere formality, it becomes a great inconvenience for voters with disabilities. Thus, some countries have started exploring how to modernise elections to provide accessibility and convenience to disenfranchised voters.

Accessibility in elections

The United Kingdom has a long history of inclusivity in elections, progressively

extending voting rights until achieving universal suffrage in a free and secret ballot. At least in theory. For people with visual disabilities, the secrecy of their vote is not guaranteed under the current voting system.

To increase accessibility, polling stations are required by law to have Tactile Voting Devices (TVD). The device consists of a plastic template that can be attached to a ballot paper. Since the template only contains the numbers of the candidates in large print and braille, voters need to memorize the number of each candidate, read the list from a large-print reference ballot or vote with the help of a volunteer. According to

a research by the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), 8 out of 10 voters using the TVD still needed the assistance of a companion or the electoral staff.

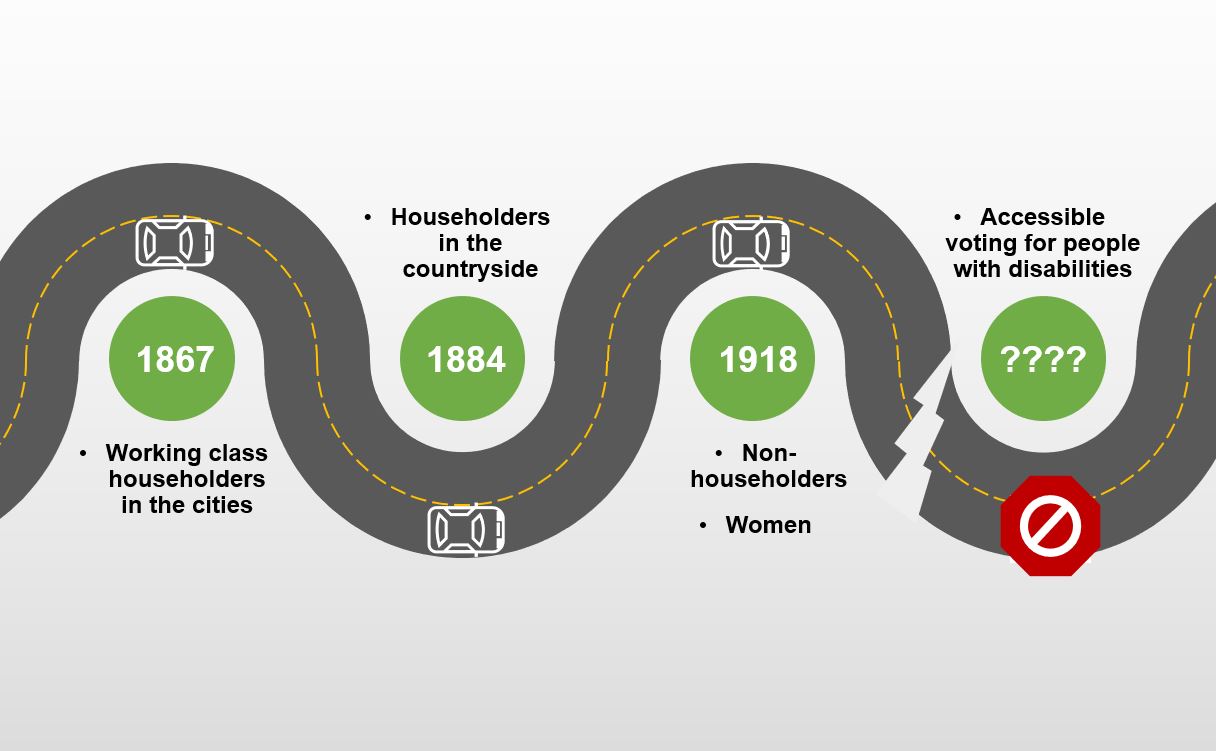

Image above shows the evolution of voting rights in the United Kingdom.

Image above shows the evolution of voting rights in the United Kingdom.

In the 2019 European elections, many disabled voters in the United Kingdom voiced their concerns over the voting alternative methods.

“This morning a polling station volunteer helped me complete my ballot. He read out the parties, I told him my vote & he made the mark. He was polite & fully aware of the procedure. However I want an accessible voting system so I can vote independently & privately”. https://twitter.com/i/moments/1136201646999068675

“I don’t use Braille and the paper was just too long for the magnifier or the tactile device I knew it would take me ages & still not be sure it was correct. I would just love an accessible voting machine”. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/10/13/rock-paper-scissors

“Can we start talking about the fact that, for blind people, the tactile voting device does not make voting independent, private or secret. We still require sighted assistance and that’s not equal rights”. https://twitter.com/j0ekenny/status/1131282424523055106

“Bass enables me to travel to the polling station independently. It’s a shame I couldn’t vote independently. The staff was very helpful, but still really #Awkward”. https://twitter.com/KAJCampaigns/status/1131610204406190083

Other voters opted smartphone applications that read texts out loud, but their privacy was still compromised:

Rachael Andrews, who has been registered blind since 2000, challenged the use of TVD in the High Court. According to the Representation of the People Act 1983, the method designated by the government must allow people with visual disabilities to vote without any need for assistance.

She argued that the device didn’t accomplish its function because voters still needed assistance to cast their votes:

“The right to vote independently and in secret is fundamental to any democratic society and it is extremely frustrating that I have had to bring this legal challenge in order to force the Government to make suitable arrangements for blind voters”

In May 2019, the High Court agreed with her complaints,

declaring the TVD unlawful and describing the current arrangements as a parody of the electoral process. Despite this ruling, the government didn’t change the TVD system in the December 2019

general elections and blind voters were deprived from secret and independent voting once again.

Is online voting a realistic alternative?

While ballot papers in Braille are often framed as a possible solution, it is estimated that

less than one percent of the population with visual impairment can read it. And with the

rise of screen reading technology, this number is expected to decrease even more in the future.

For this reason, in some regions like the

state of New South Wales in Australia people with visual disabilities have been offered the possibility to cast their votes online. Since 2011, eligible voters vote from their smartphones and computers through the platform

iVote. Thanks to this platform, voters with disabilities in NSW can vote from their homes, guaranteeing the secrecy and accessibility of the vote. The platform enables them to use screen reader tools to successfully cast their votes and operates in multiple languages.

The project was proposed after a Blind Citizens Australia survey found that 73% of voters with visual disabilities preferred to vote from home, and almost 64% selected online voting as the most accessible method. Although online voting was promoted to make elections accessible for disabled voters, the initial

viability report found that other groups of electors could benefit from voting remotely. The electoral commission finally extended the service to voters with other disabilities and citizens living more than 20km from a voting centre or traveling during elections.

The project has received a

positive response and it was reported that 81% of the users were satisfied with its efficiency during the 2019 state elections. The popularity of the application is significative, and its use from 1,1% of the total voters in 2011 to 6,22% in 2015. In 2019, the percentage over the total was almost 5%. While some security concerns have been reported, the electoral commission

maintains that the system is secure. They argue that, apart from encrypting the votes and using auditable systems, eligible voters for iVote represent a small percentage of the electorate and the incentives for their votes to be manipulated are low.

Online voting in the United Kingdom

Examples such as the NSW iVote project have fostered modernisation in elections around the world, but it seems online voting is not going to be implemented in the United Kingdom anytime soon. Despite claims for electoral reforms, the government

has rejected online voting, arguing that it is still an insecure technology and increases the risk of fraud.

The unwillingness from the government to make elections accessible is having serious consequences. Not only disabled voters feel disenfranchised and can’t be completely sure about the outcome of their vote, but some of them decide not to vote at all. It is time to listen to their stories and give them a voice, enabling their participation in elections on an equal footing.

Find out more information and ways to make the right to vote a reality for everyone

This is part of a series of blogs written by current IDS masters students and PhD Researchers. Look out for other blogs in this series, including: Barricades and democratic tsunami in Barcelona;

Muxes, the third gender that challenges heteronormativity;

That Night a Forest Flew;

Eco-anxiety and the politics of hope: a reflective opportunity to build resilience;

About Greta Thunberg and silenced environmental leaders; From alleged offenders to confessed sufferers: Participatory process in action;

Women’s struggle in Afghanistan: An Insight from a Human Rights perspectives;

Feminist Latin American movements demanding sexual and reproductive health and rights;

India’s Progressing Ambitions in Development Finance … plus others to follow on- Rwanda on a participatory theatre project, , and USAID’s digital strategy